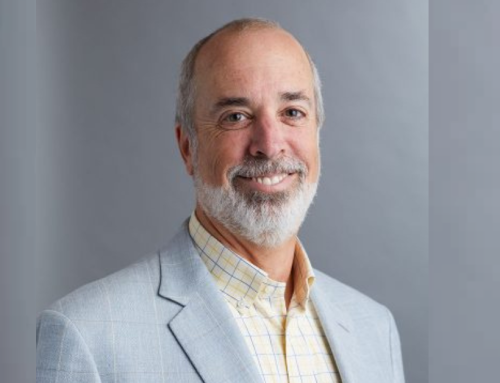

Guest: David Gelles, a New York Times journalist and author of Dirtbag Billionaire: How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave It All Away.

He’s also the author of The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America—and How to Undo His Legacy.

In a nutshell: Few business leaders are as paradoxical or as inspiring as Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard. He’s a dirtbag climber who hated capitalism, yet he built a billion-dollar company. He didn’t seem to care much about money, but he resisted sharing profits and ownership of his company with his employees for decades. He amassed a vast fortune, and then he gave it all away.

On today’s show, David Gelles and I dig into the paradoxes at the heart of Yvon Chouinard’s story and why Patagonia’s model of mission-led capitalism matters in today’s era of deregulation and dealmaker capitalism, David also contrasts Chouinard’s purpose-driven playbook with Jack Welch’s shareholder primacy capitalism, and reflects on what these two archetypes tell us about the future of business.

.David Gelles and I discuss:

- How Yvon Chouinard stayed true to his values, passions, and lifestyle as he built a billion-dollar brand and then gave it all away.

- Why Chouinard refused outside investment and employee equity despite his seeming indifference to money.

- Patagonia’s successes and failures in its mission to be an agent of change.

- What Patagonia’s brief collaboration with Walmart tells us about the fragility of corporate values.

- Comparing Chouinard’s leadership and approach to capitalism with Jack Welch’s.

- Chouinard’s lifelong friendship with North Face founder Doug Tompkins and how their careers and ideas about wealth initially diverged then ultimately converged.

- Is Patagonia’s model replicable, or is the company a true unicorn?

David Gelles on the central paradox of Yvon Chouinard:

“ This is a book that, at the heart of it, has a paradox, and it’s not one that ever gets resolved. This is a man and a company that embody two ends of a spectrum. In the outdoor community from which Chouinard came, the term ‘dirtbag’ is almost the highest compliment. It’s like a term of endearment that denotes the most hardcore athletes who are so fundamentally enamored with the outdoors and so fundamentally uninterested in materialism that they are literally content to sleep in the dirt if it means they’re closer to their next climb. And so that identity is core to Chouinard and it ultimately becomes core to the company’s identity itself. Amongst all the people who would go on to build billion-dollar businesses, perhaps Chouinard is the least likely. Not only because that’s not a natural proving ground for a multi-billion-dollar entrepreneur. But he grew up hating businessmen. He called businessmen ‘grease balls.’ He didn’t respect capitalism. And yet he becomes wealthier and wealthier, the company gets bigger and bigger, and the central paradox gets all that much harder to reconcile.”

David Gelles on how Chouinard and Tompkins influenced each other’s businesses:

“ It’s an incredible friendship, one that I argue really sort of shaped the world we live in today. Doug Tompkins was the founder of both the North Face and Esprit. They linked up early, during Chouinard’s dirtbag climbing years. They went on a series of really pivotal expeditions together, including the 1968 trip that ultimately inspired Chouinard to really found Patagonia. The mountain that they summited on that trip is the inspiration for the Patagonia logo. And it was in Patagonia, during 30 days when they were trapped in an ice cave waiting to summit that mountain that Tompkins and Chouinard really started talking about the future of their businesses. Chouinard really heard Tompkins drill into him the idea that it wasn’t enough to make climbing equipment, which is mostly what Chouinard was making at this time. Tompkins told Chouinard that he needed to get into the clothing business. That’s where he was going to make his real money. That’s where he was going to make his impact. Chouinard resisted for a few years, but ultimately, boom, Patagonia’s on the map.

“The other thing that they talked about then was ownership and control. They weren’t talking about it in terms of institutional investors, that wasn’t on their radar. But they understood and they were talking about the need to stay in control of their own businesses, how important it was not to let other people get behind the wheel, that they didn’t trust other people even then. And you fast forward to today and what a pivotal series of conversations that was.”

David Gelles on replicating Patagonia’s success:

“ No one can ever recreate Chouinard’s life. This is a guy who led a hundred lives. The adventures he had, the things he did are just extraordinary, just like an adventure movie. He was stalking wild tigers in Siberia. He got lost in the mountains of Bhutan. Crazy stuff. So no one can ever recreate his life and no company can ever recreate Patagonia. But that’s not the point. You look at his life and you look at Patagonia and you have a series of choices that individuals made that led to a bunch of really exceptional outcomes. And without trying to replicate a narrative, I think that’s the lesson. You can make certain decisions that lead to outcomes that you want to see in the world. And sometimes it requires sacrifice, and sometimes it might mean saying no to some short-term profits. But in time I really contend that those choices add up. And when expressed consistently over years and decades, that consistency in values, that solid, consistent ethical framework leads to really remarkable outcomes.”